Have you ever gotten your hands on a nature guide--birds, flowers, butterflies--and seen a species you've coveted the sight of? From the first Golden Guide to Birds I excavated in my grandparents' cool basement library as a child, I would page through and pause to admire the amazing variety of avian features on display: the colorful male American Kestrel, the ridiculously long, curving bills of assorted sandpipers, the bold patterns and slicked hairdo of Wood Ducks.

Most of all, my young imagination was captivated by the brilliant colors of the Painted Bunting (my tastes back then were...not subtle). The bright colors were nothing like the drab brown sparrows, the plain Mourning Doves that hung around the alleys and gravel lots around the neighborhood. Even our Northern Cardinal, brilliant though he is, could not compete with the cartoonish extravagance of the rainbow bird.

Needless to say, one does not encounter Painted Buntings in the upper midwest, and I have yet to see one in person. But I keep it on a mental list with other "dream" species gleaned from paging through nature guides--though I now have a realistic idea of geographic range and tend to limit my dreams accordingly.

One such critter, encountered in the pages of a butterfly guide, is the American Snout (Libytheana carinenta)--a curious specimen with (as you might guess) a prominent snoutlike structure projecting from its head, and mottled brown wings with ragged edges that make it look like a dried leaf with the "snout" as its petiole. I am charmed by prominent snoots, be they on greyhound dogs, anteaters, tapirs, elephant shrews, echidnas....a butterfly that not only had a snoot but was named for it was right up my alley.

And conveniently, their range extends over much of the eastern U.S., including Iowa, so there was a good chance I might encounter a Snout (they don't overwinter here, but populations from the southern U.S. will migrate north into our area and beyond in the summer*). Less conveniently...they are not as large and flamboyant as our Monarchs and other butterflies that get all the press, and their sneaky camouflage seemed like it would be a challenge to spot.

American Snouts use hackberry trees as hosts for their larvae, those warty-barked champions of many a caterpillar. In addition to American Snouts, hackberry trees are hosts for Mourning Cloaks, Hackberry Emperors, Tawny Emperors, and the curiously named Question Mark. Not just a tree for butterflies, the hackberry's eponymous fruits are eaten by woodpeckers, robins, pheasants, and several other birds.

But back to the American Snout....

Beyond making note of its distinguishing characteristic and its affinity of hackberry trees, I don't have the slightest idea of how to find a particular butterfly. Other butterflies I've encountered have all followed the same process: hang around flowers, maybe see a butterfly, take a picture and identify the butterfly. So my encounter with an American Snout was left in the hands of fate.

As luck would have it...the Sycamore Greenway delivered. As it always delivers. Not always what I'm looking for when I'm looking for it, but on its own time.

|

Warty bark of

hackberry tree

|

I had left my bicycle parked at the Sycamore Apartments and, going to unlock it, a butterfly fluttered off it and alighted again on the seat. Out of habit I froze and peered carefully, and saw a big long snoot! An unmistakable snoot! I didn't have my camera but carefully, slowly, pulled my phone from my purse and snapped a few shots, inching closer with each one. Eventually it spooked and flew off to a neighboring bicycle, but not before I had my documentation.

It was just a little scrap of a butterfly, with its mottled brown wings. The forewing occasionally slipped forward, revealing a large orange blotch close to its body, with smaller white spots toward the outside edge. The long, pointy snout was everything I'd hoped for.

That snout is not technically a snoot, or nose, but rather a set of labial palpi,

a feature all butterflies and moths have in varying shapes and sizes (few as

pronounced as those of the American Snout) which actually seem to

function similarly to a snoot: the labial palpi sense carbon dioxide,

which may help with detecting nectar and its concentration in flowers

for foraging.

Their caterpillars are small and green, with a thin yellow racing stripe down the side and tiny, pinprick yellow spots. There are usually two broods a year, so even if they don't overwinter in our area there may be caterpillars from the second brood wandering about. Perhaps, having lucked into an American Snout butterfly encounter, I can redouble my efforts to locate a caterpillar. You can be sure I will be inspecting the leaves of the hackberry trees along the trail this summer!

...

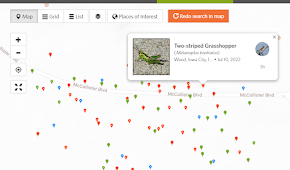

Serendipitously, the next day as I was visiting the McCollister weeds I happened upon ANOTHER American Snout, which kindly posed for more photos:

|

Forgive the quality...this was the only shot I

captured as it quickly fluttered its wings. |

*According to the Missouri Department of Conservation, American Snouts migrate to that state starting in May, but the Illinois DNR claims they overwinter. Most resources mention that they overwinter in the southern part of their range, but neglect to mention exactly what constitutes "southern part".